Molecular hybridization strategy for tuning bioactive peptide function ...

When Cough 'goes To Your Chest' It Doesn't Mean You Need A Doctor

WHEN I was on a hospital respiratory ward earlier in my career I worked briefly with a respiratory consultant who had developed a rather awkward phobia.

I was told she was morbidly afraid of phlegm. To me, that's a bit like Michael Flatley being afraid of dancing or Lionel Messi harbouring an unwavering fear of footballs.

To be fair though, phlegm is pretty gross. Even the word, in all of its onomatopoeic glory, sounds unsavoury.

Its origin lies in the ancient Greek words for heat or inflammation. As it turns out, this was quite an apt association. It's a shame then that they diverged from that promising start by inventing the theory of the four humours, a theory which became the accepted norm for the next 2,000 years or so.

I often refer to this idea of the four humours — the supposed balance of yellow bile, black bile, phlegm and blood being vital to one's health.

An excess of phlegm in the classical sense meant one would become apathetic and indifferent. This is something that lives on in the adjective "phlegmatic" to describe someone who has an unemotional demeanour.

But in no way was it the tangible phlegm that we know and love today.

Mucus and phlegm are often used interchangeably but there is a slight difference speaking technically. While mucus is the clear gel-like substance that lines and protects the cells and surfaces that line the entrances and exits of our bodies, phlegm adds to it all the debris produced when these surfaces become inflamed, alongside breakdown products of viruses or bacteria and the white blood cells that are fighting them.

In other words, it tends to come into existence when there is infection.

There's a lot of that going around at the moment. Over the past month or two, GP surgeries have noted a sharp increase in the number of people presenting with coughs, colds and sore throats.

Public Health estimates that the acute cough costs the UK economy around £979 million annually. About £104 million of this is due to the burden it places on our healthcare system.

I wasn't around 100 years ago but I get the sense that people then would just get on with things and allow these mostly viral infections to pass.

That was in the days before antibiotics. More recently, a worrying culture has developed in which we have little patience for these infections and so, in this society of immediacy, we expect these illnesses to be cured with antibiotics.

Every year I am surprised at how quickly people seek help from doctors due to their coughs and colds.

There are a few classic lines we hear almost every day. One common one is, "I've had a cough for a week and now I think it's gone to my chest." Another is the declaration that "my phlegm has turned green."

There seems to be some unwritten rule that this therefore means we need antibiotics from the doctor. It doesn't.

I have written about antibiotic resistance before so I won't labour things too much.

One public health survey found that 40 per cent of the general public believed antibiotics would help a cough with green phlegm get better more quickly than that with white phlegm.

The green phlegm thing, however, is a myth. The green colour is present in infections due to a certain product produced by the white blood cells that fights infection.

Infections can of course also be caused by bacteria, which are susceptible to antibiotics. But the vast majority of the illnesses circulating are caused by viruses and are therefore not susceptible to antibiotics (as I hope readers already knew).

What's more, it is not unusual for them to last three to four weeks. I admit, having a nasty upper respiratory tract infection is not very nice but we must gain some perspective on when we should and shouldn't be intervening with scarce medical resources for something that will get better on its own.

An antibiotic may work against a mild bacterial infection but even this only by knocking perhaps 12 hours off the symptoms.

At the other end of the scale, a serious pneumonia can kill someone unless an antibiotic is used. It's no use, however, if that antibiotic has been used so much within a community that the bug causing the pneumonia is resistant to it.

The natural course of an infection often involves a sore throat, runny nose, headache, body aches and temperatures. This can last a week or so.

Initially the cough may be dry and the airways may feel all bunged up. However, when things loosen, the cough can sound wetter, you may start to produce phlegm (classed as sputum when expectorated) and it may sound lower down on the chest.

That tends to be around the time people phone in concerned that it has "gone to my chest".

In reality, it just means it has gone on to the next phase of infection and the body is responding appropriately with its natural immune system.

People are also often concerned their cough has turned into a "chest infection". This is a bit of an umbrella term that could encompass a bad pneumonia or a viral bronchitis. It is therefore not in itself a reason to push the antibiotic button either.

At the end of the day, coughing gets the phlegm out of the body, either into the air or via the stomach where all the viruses or bacteria are killed.

Patients should consider all these issues when considering seeking help for these illnesses.

Furthermore, GPs must also prescribe responsibly. It is easy for a physician to just give someone antibiotics even when not really required, thereby validating often inappropriate requests for GP review.

In reality, rest, fluids and time is the best course of action.

There is a difficult balance here because some people can become really quite ill with respiratory infections.

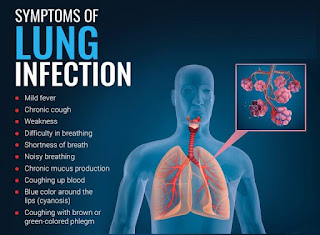

Signs that they may require treatment include feeling very short of breath, producing consistently red sputum (as opposed to flecks of blood from a burst vessel due to forceful coughing), confusion, or signs of deoxygenation such as blue lips.

A lot of people will have oxygen saturation probes lying around since covid and these can be used to check how well the blood is being oxygenated. Anything above 92 per cent is okay but below that, it is important to get checked.

Anyone with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or who has other significant long-term health issues, or is a child under five years of age should have a lower threshold to get checked.

If you don't have any of these more serious indicators, you really shouldn't be contacting the GP.

It is no secret that the health service is creaking. We are lucky in this area to have well-staffed and efficient surgeries. Some other areas are not so lucky. GP appointment waits are often the butt of jokes and there are stories of some surgeries not being able to offer appointments in any form for several weeks even before cough and cold season begins.

In order to maintain the high standards that our local surgeries set themselves, I'm sure that I speak for other colleagues when asking people whose cough has "gone to their chest" or whose phlegm has turned green, to consider carefully whether there really is a role to play for a GP.

'; var fbDiv1 = document.GetElementById('fb-div-unique_185158'); if (!FbDiv1) { // add only once var sDiv1 = document.GetElementById('unique_185158'); if (sDiv1) { sDiv1.InsertAdjacentHTML('afterend', fb_div_str); } else { console.Log('insert facebook comment: div not found'); } } else { // console.Log('insert facebook comment unique_185158: fb-div already exists'); } } }; generateFacebookComment_unique_185158();

China's 'White Lung Syndrome' Resurgence Sparks Concerns; Here's Everything You Need To Know

China is grappling with a puzzling health crisis as face masks and social distancing rules make a comeback, marking nearly four years since the initial onset of the global pandemic. An enigmatic outbreak has caused a surge in hospitalizations, particularly among children, with cases presenting a severe respiratory illness labeled as "white lung syndrome."As Beijing and Liaoning witness a surge in afflicted youngsters, concerns heighten over this newly emergent health threat, marking the first winter post the lifting of Covid restrictions in China. The World Health Organization (WHO) seeks clarifications from Chinese authorities regarding the nature and scope of this concerning situation.

The recent outbreak has raised fears among families, with patients enduring prolonged waits in urgent care facilities. Despite the escalating concern, Chinese officials have downplayed the severity, attributing it to typical winter ailments rather than acknowledging a novel virus.According to Ministry spokesperson Mi Feng, efforts are underway to bolster healthcare provisions by expanding clinic accessibility, extending service hours, and augmenting medicine supplies. Urging local authorities to take proactive measures, Feng emphasized the imperative need for fever clinics catering to vulnerable demographics like the elderly and children, advocating for increased vaccination coverage. Additionally, the recommendation to wear masks and maintain social distancing remains pivotal.In response to the outbreak, directives have been issued to safeguard densely populated areas such as schools and nursing homes, aiming to curtail the spread of the illness. Reports from The Sun indicate a staggering daily admission of approximately 7,000 patients at a children's hospital in Beijing.

What's causing it and what we need to know to battle it Mycoplasma pneumonia, though not a recent bacterium, has surfaced prominently within Chinese communities amidst this outbreak. Distinct from conventional bacteria, its viral-like behavior facilitates swift person-to-person transmission, infiltrating both lung sides and instigating severe coughing and breathing complications. The bacterium's resurgence, particularly among vulnerable groups, raises questions regarding potential mutations or alterations in its behavior following the cessation of stringent Covid containment measures. For years, medical practitioners have treated this bacterial infection using antibiotics within the PCR guidelines. In China, it has circulated alongside the HN92 virus, exhibiting a unique interaction within the ecosystem. Understanding Spread and Symptoms While not as rapidly infectious as a virus, mycoplasma pneumonia swiftly targets the throat, nasal cavities, and descends to the lungs, culminating in pneumonia. Vigilance against exposure to individuals exhibiting persistent coughing or sneezing in confined spaces is crucial. Recognizable symptoms encompass red blood cell breakdown, skin rash, joint pain, and a higher risk of contraction during winter. Children commonly manifest symptoms like nasal congestion, sore throat, watery eyes, wheezing, vomiting, and diarrhea.Prevention Measures and Risks Strengthening immunity through balanced diets, exercise, ample rest, and avoiding crowded spaces remains pivotal. The adoption of masks in social settings acts as a shield against diverse respiratory illnesses. Emphasizing proper hygiene practices, including frequent hand washing after contact with infected individuals, is recommended.The infection poses a risk to all age groups, particularly children, the elderly, or individuals with compromised respiratory systems. Prompt medical consultation is advised upon experiencing symptoms such as cough, fever, or breathing difficulties. Early diagnosis significantly enhances recovery prospects, while those with pre-existing respiratory issues face a higher susceptibility to severe infections.

Efficacy of Antibiotics and Medical Intervention Several antibiotics, including Azithromycin for children and Doxycycline or Moxifloxacin for adults, exhibit efficacy against the infection. However, seeking medical advice before medication is crucial. Medical practitioners rely on stethoscope examinations to detect abnormal breathing patterns, often supplemented by chest X-rays or CT scans for a comprehensive diagnosis.Disclaimer Statement: This content is authored by a 3rd party. The views expressed here are that of the respective authors/ entities and do not represent the views of Economic Times (ET). ET does not guarantee, vouch for or endorse any of its contents nor is responsible for them in any manner whatsoever. Please take all steps necessary to ascertain that any information and content provided is correct, updated, and verified. ET hereby disclaims any and all warranties, express or implied, relating to the report and any content therein.

Child Pneumonia And Whooping Cough Cases In The Netherlands Soar To A Three-year High

» More tags « Less tagsWednesday, 29 November 2023 - 20:20

There is an increase in pneumonia and whooping cough cases among children in the Netherlands. According to weekly data from the Nivel research institute, the number of cases has significantly risen in recent weeks.

Whooping cough, also known as pertussis, is a contagious illness characterized by a severe cough that ends in a "whooping" sound when breathing in. Pneumonia is a lung infection that can make breathing difficult and cause symptoms like coughing, fever, and chest pain.

Last week, approximately 10 out of every 100,000 children aged 0 to 14 in the Netherlands visited a general practitioner for whooping cough. This figure is more than double that of the previous week. The number of children visiting doctors for whooping cough is higher than in the past three years, with this year's peak being three times higher. These numbers have been increasing since early October.

Pneumonia cases are also rising. "There are a striking number of children and young people with pneumonia," Nivel reported. Last week, 130 out of every 100,000 children aged 5 to 14 presented such symptoms to a doctor. This rate is over twice the highest number recorded last year, with general practitioners noting more pneumonia cases among teenagers and young adults than in previous years.

While the number of pneumonia cases among children aged 0 to 4 years has been increasing since mid-September, these figures remain lower than those before the Covid-19 pandemic.

Nivel did not provide explanations or conclusions regarding these trends in its weekly report.

Last week, AD reported that China was implementing extra measures due to a surge in the number of child pneumonia cases in the northern part of the country. The RIVM stated that it was "not yet possible to say" whether the recent increase in the Netherlands was linked to the situation in China. "We do not know, but we do not assume so," a spokesperson said.

Comments

Post a Comment